MIM

What Is MIM?

Process Overview

When to Use MIM

General Guidelines

Technology Comparisons

Materials Range

Materials List

Design Guidelines

Designing for Manufacturability

Uniform Wall Thickness

Thickness Transition

Coring Holes

Draft

Ribs and Webs

Fillets and Radii

Threads

Holes and Slots

Undercuts

Gating

Parting Lines

Decorative Features

Sintering Support

Secondary Operations

Process Overview

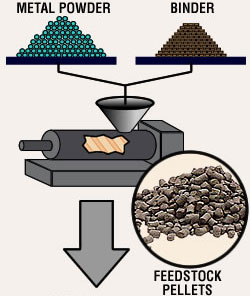

1. Feedstock Mixing and Granulating

The first step in the MIM manufacturing process is the production of the feedstock that will be used. It begins with extensive characterization of very fine elemental or prealloyed metal powders (generally less than 20 μm). In order to achieve the flow characteristics that will be required in the injection molding process, the powder is mixed together with thermoplastic polymers (known as the binder) in a hot state in order to form a mixture in which every metal particle is uniformly coated with the binder. Typically, binders comprise 40% by volume of the feedstock. Once cooled, this mixture is then granulated into pellets to form the feedstock for the injection molding machine.

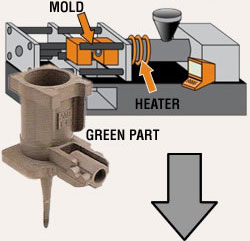

2. Molding

The next step is the molding of the part in a conventional injection molding machine. The feedstock pellets are gravity fed from a hopper into the machine’s barrel where heaters melt the binder, bringing the feedstock to the consistency of toothpaste. A reciprocating screw forces the material into a two-part mold through openings called gates. Once cooled, the part is ejected from the mold with its highly complex geometry fully formed. If necessary, additional design features not feasible during the molding process (undercuts or cross holes, for example) can be easily added at this stage by machining or another secondary operation.

3. Binder Removal

The ejected as-molded part, known as a “green part,” is still composed of the same proportion of metal and polymer binder that made up the feedstock, and is approximately 20% larger in all its dimensions than the finished part will be. The next step is to remove most of the binder, leaving behind only enough to serve as a backbone holding the size and geometry of the part completely intact. This process, commonly referred to as “debinding,” may be performed chemically (catalytic debinding) or thermally, which in some cases may involve a solvent bath as the initial step. The choice of debinding method depends on the material being processed, required physical and metallurgical properties, and chemical composition. After debinding, the part is referred to as a “brown part.”

4. Sintering

In this process, which is performed in the highly controlled atmosphere of either a batch furnace or a continuous furnace, the brown part is staged on a ceramic setter and is then subjected to a precisely monitored temperature profile that gradually increases to approximately 85% of the metal’s melting temperature. The remaining binder is removed in the early part of this cycle, followed by the elimination of pores and the fusing of the metal particles as the part shrinks isotropically to its design dimensions and transforms into a dense solid. The sintered density is approximately 98% of theoretical. The end result is a net-shape or near-net-shape metal component, with properties similar to those of one machined from bar stock. Of course, if necessary, post-sintering operations such as coining, machining, heat treating, coating, and others, may be performed on the part to achieve tighter tolerances or enhanced properties.